Whether you want to buy or to sell jewelry or watches, the first step in figuring out value is to identify what it is, when and where it was made, and by whom. A maker's mark can help but if jewelry has hallmarks, this process is almost foolproof.

Pinpointing maker and metal content is often pretty easy. Many of the world’s major jewelry- and watch-making centers require that makers register their marks so they can be tracked. But a maker’s mark is not the same as a hallmark.

A maker’s mark is a personal trademark for the individual responsible for the precious metal content of the piece. A hallmark is a separate stamp made by an assay office – in countries that have an assay office. Not all do.

.webp?width=600&height=384&name=Tiffany_jewels_at_Christies_2014%20(1).webp)

This group of gold jewels from Tiffany & Co. sold at Christie's London in 2012 for $2,602, with the help of their marks - a brooch signed Paloma Picasso, Tiffany & Co., with maker's mark T&Co., and heart pendant and chain signed Tiffany & Co. and De Beers. London hallmarks date the brooch to 1994, the rest to 1989.

In many cases, as with French jewelry or Swiss watches, you’ll find both maker’s marks and hallmarks. But many countries including the U.S. do not have a hallmarking system. Although reputable firms mark their jewelry, registering marks is not required. As a result, there is nowhere to research the identity of a signature or mark.

Buying jewelry from countries with a hallmarking system offers more of a guarantee, if you can decipher the marks. Hallmarks vary from one country to the next. You’ll find animal heads on French jewelry, for example, a numerical code on British jewelry, and a combination of symbols and numbers on Russian jewels.

How do you begin deciphering the code? A good appraiser can help and it’s always wise to buy from trusted dealers who offer written guarantees. But any serious collector should have a jeweler’s loupe and a decent hallmarking guide, and start learning to decipher the code.

.webp?width=500&height=433&name=World_Hallmarks_guide%20(1).webp)

World Hallmarks is an exhaustive guide to jewelry hallmarks used worldwide. It's a bit much to lug around to estate sales but very handy to have on your shelf.

Joyce Jonas, a NYC-based jewelry historian and regular on the Antiques Roadshow, says she can usually tell whether a piece of jewelry was made in France or Italy just by examining the way it was made. “Then I turn it over and look at the marks,” she says. “I’m usually right.”

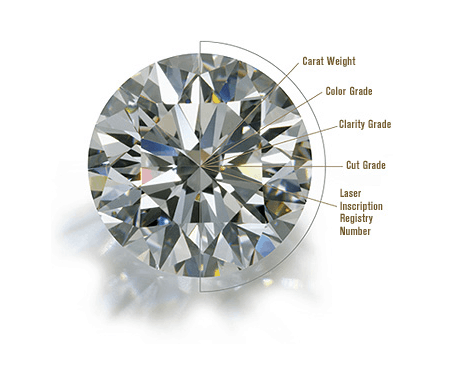

In most European countries, a system is set up for hallmarking fine jewelry and watches, where an assay office tests each piece and puts their official stamp or hallmark on it to guarantee metal fineness, similar to the way diamonds are certified by the Gemological Institute of America (GIA). Hallmarks can also tell you, in some cases, where and when a watch or jewel was made, Maker's Marks.

In countries with an assay system in place, it’s illegal to sell fine jewelry and watches without a hallmark – which is why Tiffany & Co. sends jewelry to London to have it hallmarked. Doing this doesn’t cost that much and allows them to offer their jewelry for sale on the European market.

A sample of what the Birmingham Assay Office (founded in 1773) offers in terms of educational resources

The UK is among 19 countries that belong to the Hallmarking Convention, formed in 1976 to create a set of standards for assay offices so jewelry wouldn’t have to be re-tested every time in crossed borders. But even in Europe, jewelry hallmarking isn’t guaranteed. Germany doesn’t have hallmarking. A few countries, like Austria and Norway, have optional hallmarking. Italy doesn’t require hallmarks but has a more formal registration for makers than the U.S., using a numeric system.

When buying or selling valuable antique or period jewelry, having a hallmark – instead of just a maker’s mark – can make a critical difference. “People who collect by maker – Van Cleef & Arpels, Bulgari, Tiffany, Cartier – want to see that maker’s mark on the piece,” says William Whetstone, jewelry appraiser and co-founder of the Hallmark Research Institute. “But in order to prove it was a genuine Cartier piece made in France, you want to see the French hallmark as well.”

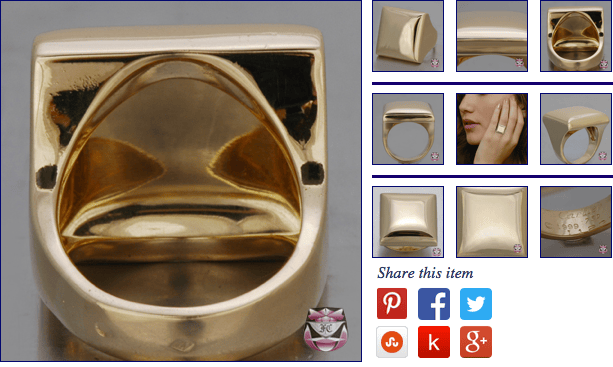

This Cartier gold ring for sale at Fay Cullen shows a close-up of the marks inside the shank, including year made (1999), fineness of metal (750 meaning 18k gold) and maker's mark for Cartier beside an eagle's head (indicating French provenance).

Sometimes metal marks alone provide a key to the where and when of an old piece of jewelry. In Europe, pure 24-karat gold is marked 1000 fine, while 18-karat gold is 750, meaning 75 percent. If it was made in England before 1975, 18k gold will be stamped 18ct or 18c.

On fine jewelry made in the U.S., you will usually find a mark identifying precious metal content, but because there is no official system in place to verify this, it’s not uncommon to find a piece of jewelry stamped with an inflated weight. Larger firms with established brands are not likely to indulge in “under-karating,” but mass-market manufacturers sometimes will – one reason to stick with recognizable names and get familiar with their maker’s marks.

Stamp a piece of gold jewelry “18k” when it’s really 15- or 16-karat and you’ve just inflated its value by 10 to 15 percent. When the price of gold hit $1,900 a couple years ago, that one karat difference represented a serious amount of money. Even with the price of gold at $1,200 an ounce, 10 percent of a 100-ounce piece of gold is $12,000.

Whetstone has heard estimates that as many as one in every three gold items made in North America is at least slightly “under-karated.” It’s impossible to verify this, but it’s probably safe to say: Buyers should beware.

Read more...

How Gold Buyers Decide On A Price | Selling Gold Jewelry

Colored Diamonds Set World Records at Auction

Silla: Korea's Golden Kingdom Opens at the Met

What You Need to Know About Jewelry Hallmarks (The Jewelry Loupe)

Cartier Set to Dazzle at the Denver Art Museum